Apps

The Daily Edit app looks to make sense of the media

This iOS and Android app cuts through the noise and quantifies the accuracy and completeness of news articles.

Just a heads up, if you buy something through our links, we may get a small share of the sale. It’s one of the ways we keep the lights on here. Click here for more.

The internet has been a bad thing for journalism. Yes, I appreciate the irony here. I’m a journalist who writes for websites.

It’s like an automotive writer railing about the internal combustion engine. Or a physicist whinging about Einstein’s Theory of Relativity.

But it’s true. Thirty years ago was journalism’s halcyon era. It was an industry that offered a living wage, job stability, and the opportunity to break important stories.

A tale of media misery

The internet changed that for reasons that are too varied to cover (exhaustively) here. For the first time in history, newspapers were forced to compete with technology companies for ad revenue. It wasn’t a fair fight.

Subscriptions declined. New startups rendered the classifieds and lonely hearts pages obsolete. Newsrooms closed.

Thousands of talented muckrakers left for better-paid PR, marketing, and communications roles.

Publications haven’t gone anywhere. Journalism is still fundamental to a thriving democracy. But it’s suffering, often with consequences for readers.

Overworked authors can miss vital details, make mistakes, or fail to update their articles to reflect new developments.

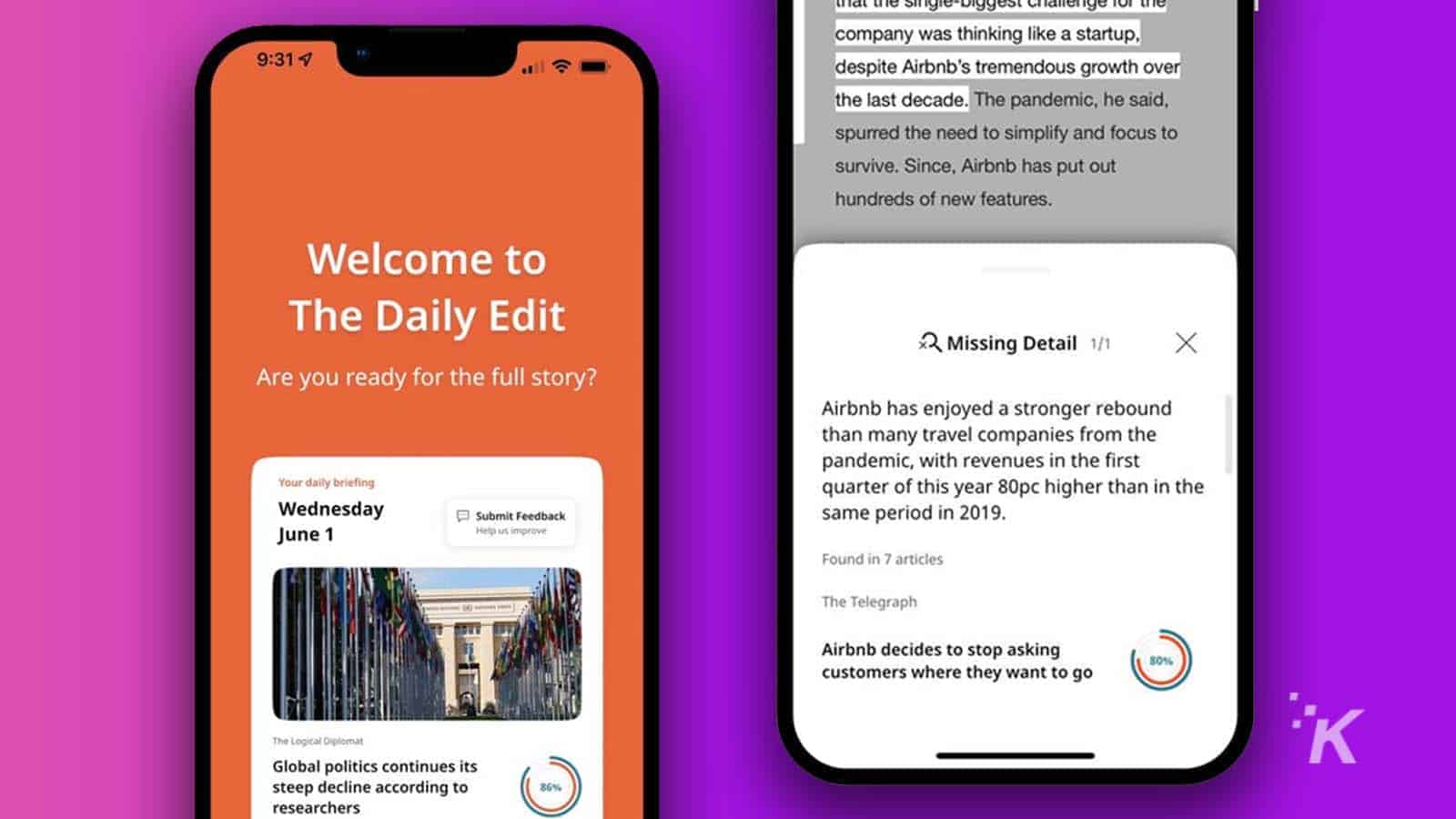

Enter The Daily Edit. This iOS and Android app cuts through the noise and quantifies the accuracy and completeness of news articles.

It aggregates content from a broad array of sources based on the user’s interests and, within articles, highlights specific paragraphs with missing context, or where to find sources with more detail.

Making sense of the media

The 2016 election of Donald Trump (and, to a lesser extent, the Brexit referendum) highlighted several weaknesses in the global media ecosystem.

Overnight, terms like “filter bubble” and “fake news” entered our collective lexicons.

Naturally, the technology world took notice. Countless news apps entered the fray, making bold promises about their ability to curate only the best sources or how they can show readers both sides of a story.

For obvious reasons, most failed. People like their filter bubbles. If you skew left, you don’t want to read Fox News. Similarly, conservatives aren’t interested in what CNN has to say.

The Daily Edit doesn’t make any claims to political neutrality or a lofty vision to break the shackles of division in the anglosphere.

Its goal is more simple than that. It wants people to have the full facts behind a story. When you sign up, it doesn’t ask where you lean politically. It asks about what stories you care about.

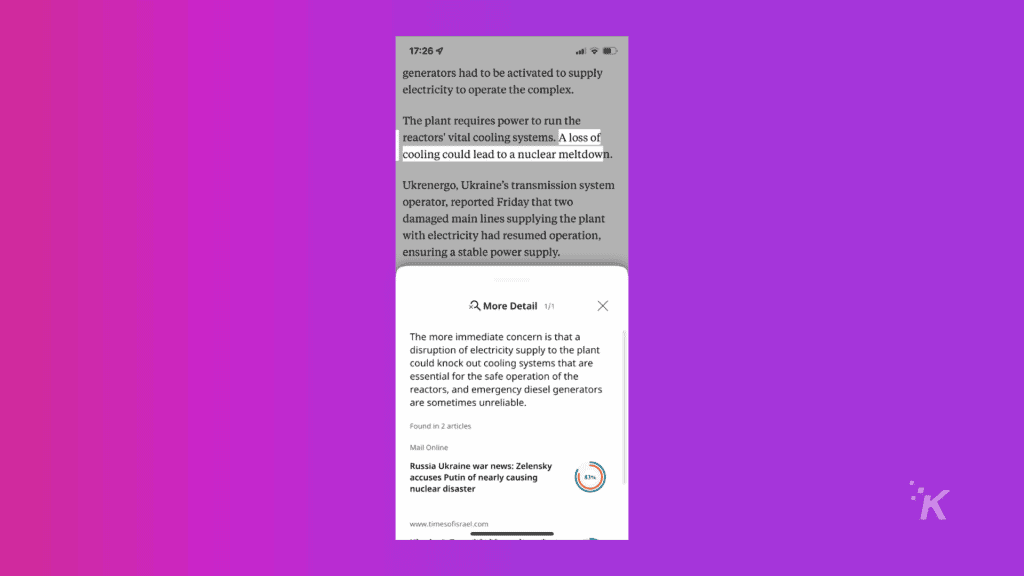

The app’s cleverest feature is the ability to highlight key details within a story and point to other sources. This context is often accompanied by a short commentary written in a plain, unsensationalized style.

In fact, detail and accuracy are the only metrics it seems to care about. The political slant of a publication doesn’t seem to influence its recommendations.

For example, in one article published by ABC (a relatively apolitical entity), the app suggested I check out another piece by the right-leaning Daily Mail. And that’s good. Facts have no political persuasion.

The media quality sniff test

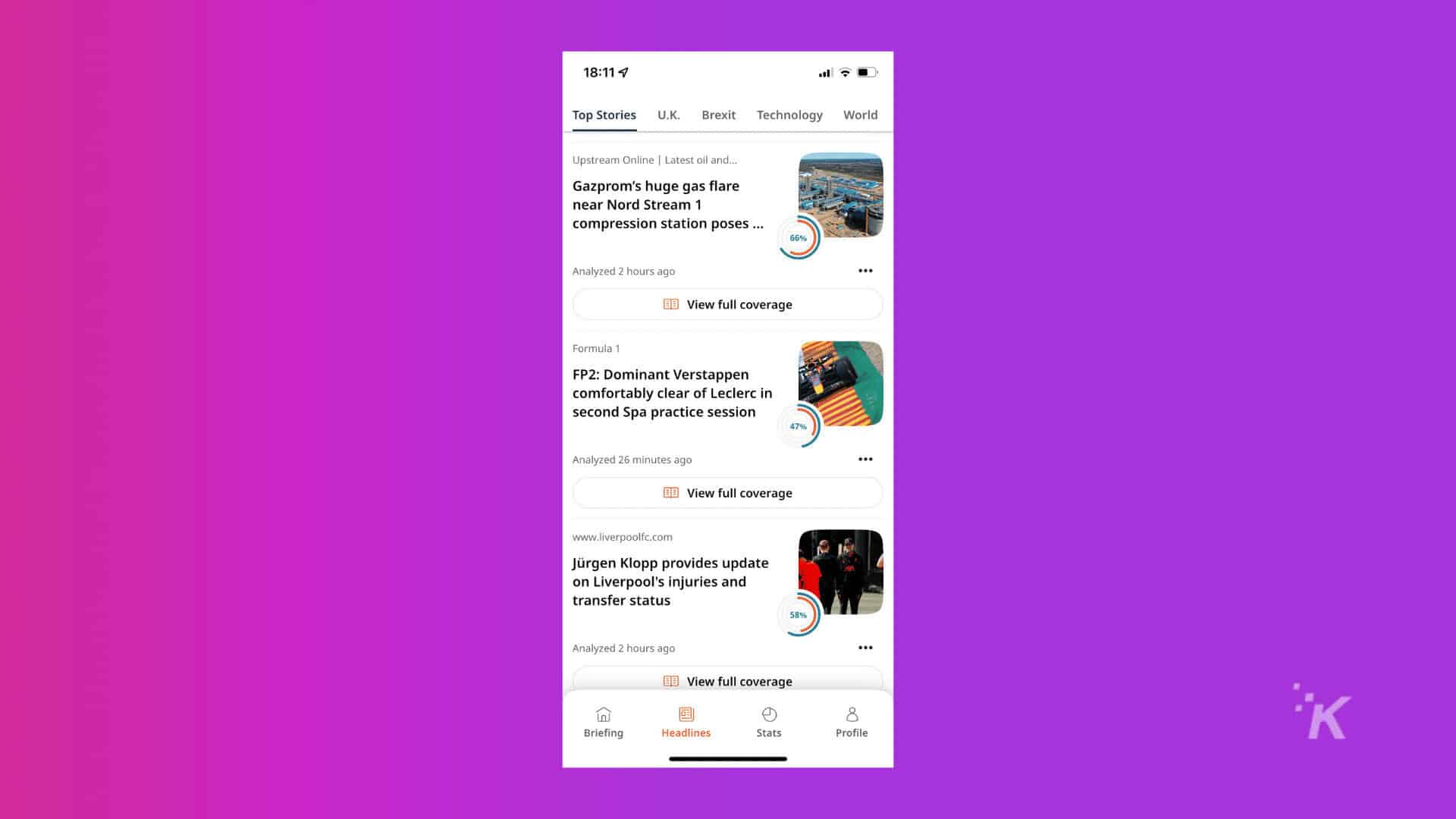

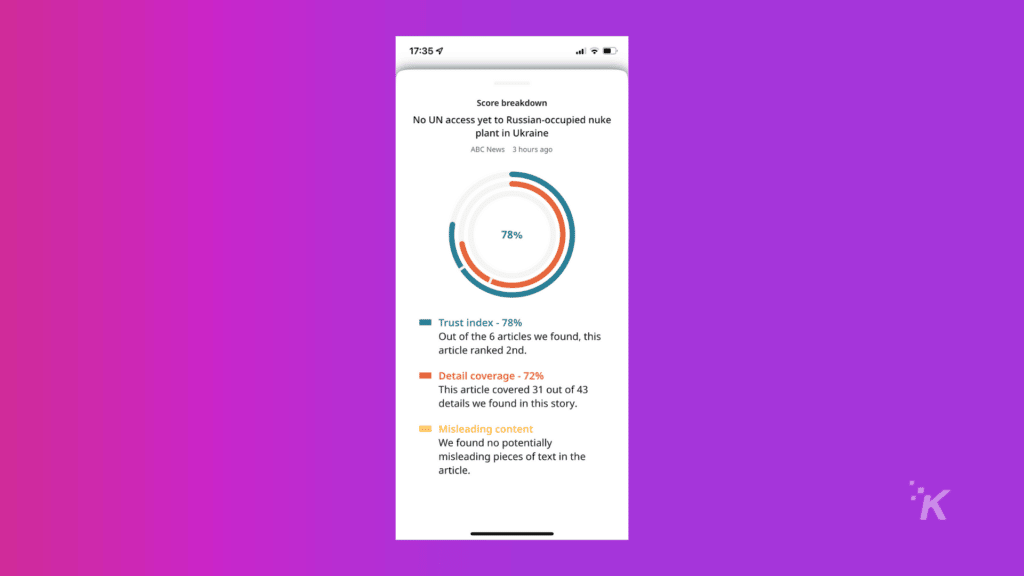

The Daily Edit measures articles against three benchmarks: trust, detail, and misleading content. These factors combine to create an overall quality score.

This begs the question: How does it make these determinations? The Daily Edit offers a relatively high-level overview of how these elements work.

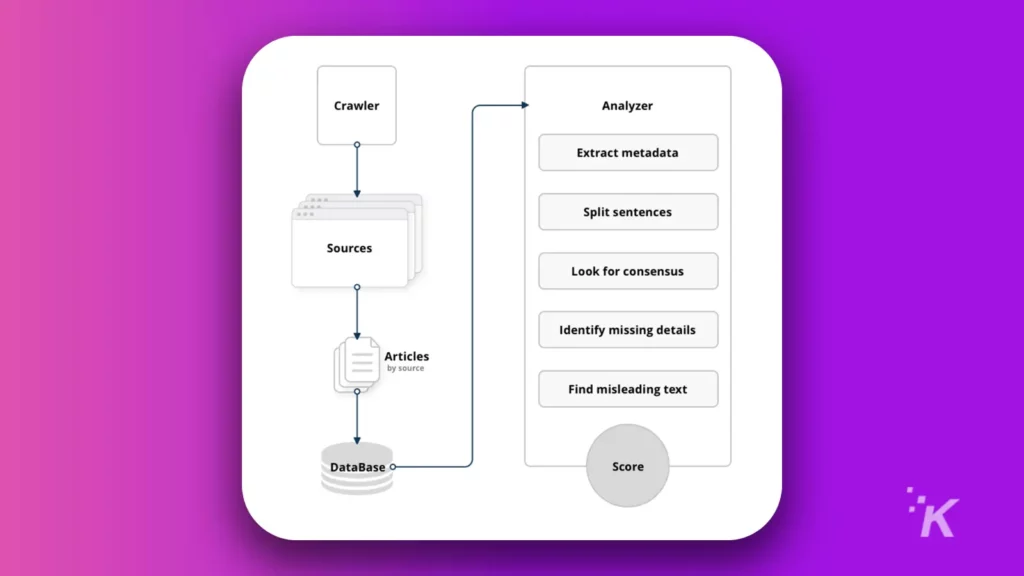

The company scrapes the Internet for news stories. Using Natural Language Processing, The Daily Edit identifies common facts across publications.

These facts are quantifiable. A story may have 50 identified elements, and an article may only mention 30 of them. That’s how it measures completeness.

Misinformation is a trickier beast to measure. Lies are inherently self-replicating. If repeated enough, they become an accepted reality. As the saying goes: “A lie can travel halfway around the world before the truth can get its boots on.”

The Daily Edit doesn’t scan for hyperbole or opinion. It looks for the other telltale signs of a fudged fact. Limited or anonymous sourcing. Scare quotes. You get the idea.

Interestingly, The Daily Edit doesn’t weigh misinformation and incompleteness equally. Completeness accounts for 80 percent of the trust ranking. Misinformation accounts for 20 percent.

A story with every possible detail and no misinformation will get a perfect score.

Or, put another way: The Daily Edit will recommend a detailed article with some misleading elements over something that’s thinly written. As the company explains on its webpage:

“Over time we’ve decided to favor articles with more coverage, since more coverage tends to lead to a more balanced view of the story set.”

The Daily Edit walks a tough line. But I also understand where they come from. Completeness is easier to measure accurately. The app’s entire reason for existence is to provide readers with the maximum amount of information possible.

With that in mind, their approach makes a lot of sense.

Conclusion

The Daily Edit isn’t here to change your mind. It doesn’t want to pop your filter bubble. It just wants to give you facts. It’s a very grown-up, dispassionate way of looking at the media world.

And it doesn’t patronize you, either. The Daily Edit operates under the assumption that you’re smart enough to identify elements of sensationalism or hyperbole.

It recognizes that, given enough sources, you can determine the truth behind a story.

In my decade-long career as a tech journalist, I’ve witnessed many apps try and remake the news business. The Daily Edit is the first I’ve genuinely liked. You can learn more here.

Have any thoughts on this? Carry the discussion over to our Twitter or Facebook.

Editors’ Recommendations:

- Duolingo will now teach you elementary-level math

- Microsoft Outlook app showing more ads on iOS and Android

- This new app beeps whenever Google tracks your computer

- MoviePass is coming back with beta access starting in September