Apple

Don’t be fooled by Apple’s embrace of ‘Right to Repair’

It’s a step in the right direction. But it doesn’t overshadow Apple’s appalling behavior, both in the past and now.

Just a heads up, if you buy something through our links, we may get a small share of the sale. It’s one of the ways we keep the lights on here. Click here for more.

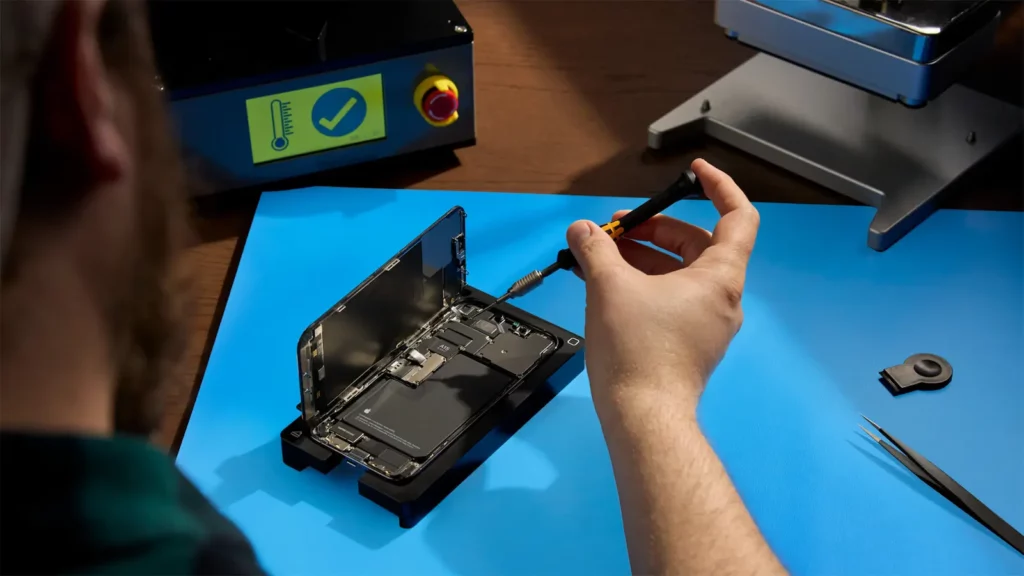

Apple’s self-repair service for Macs is now live. Individuals can now buy the components necessary to fix their broken computers – no Genius Bar trip is required.

Well, almost. As with the equivalent iPhone program, Apple only provides whole components. Put another way: if a single chip on a logic board fails, you must replace the entire unit. You can’t simply replace that one chip.

Before I go on, I want to make something clear. I think this is a welcome move. It’s flawed, sure. There’s a lot to criticize (and I will). But it’s also a step in the right direction.

But it doesn’t go far enough. And it doesn’t make up for ongoing Apple’s attacks on the independent repair sector.

Apple’s ongoing quest for absolute control has produced disastrous consequences for the environment, consumers, and small businesses. And I’m not willing to overlook them.

Historical Background on the Right to Repair movement

Apple was once the Right to Repair movement’s most vociferous opponent. And its most effective.

With limitless resources, Apple could afford to lobby right-to-repair legislation across local and national statehouses.

The message that the “right to repair” is inherently dangerous was core to its lobbying. If consumers could repair their equipment, they may harm themselves or their devices.

In the first five months of 2021, 27 states considered Right To Repair legislation. More than half failed. Many were dismissed at the committee stage. They didn’t even get a vote from lawmakers.

Obviously, Apple has changed its tune here. After previously describing user-made repairs as “dangerous,” it is now willing to let you take the risk.

I’m a cynical person. I suspect it’s merely responding to the Right to Repair movement’s rising tides. Apple couldn’t win by lobbying alone.

The movement has already scored several major victories in Europe, the UK, and the US (state-wide and federal).

Apple — and the wider technology industry — may win the occasional battle. But the war? It lost that years ago. The writing is on the wall.

Whatever. Motivations don’t matter. The reality is that users and independent repair providers now have the tools and components they need to fix their stuff.

But that shouldn’t overshadow Apple’s continuing shenanigans, nor the inherent weaknesses in the Apple self-service repair program.

How Apple Frustrates Independent Repairs

Apple is a big company. It’s the world’s most profitable consumer technology brand. In the quarter ending June 25, it sold over $40bn iPhones and $7.3bn Macs.

In normal times, that’s impressive. During a supply chain crisis and a recession, it’s nothing short of outstanding.

Money is power, and Apple holds sway over its suppliers. It can demand exclusivity for certain components — even those created by third parties. And it does.

This limits the ability of repair shops to acquire essential components for board-level repairs.

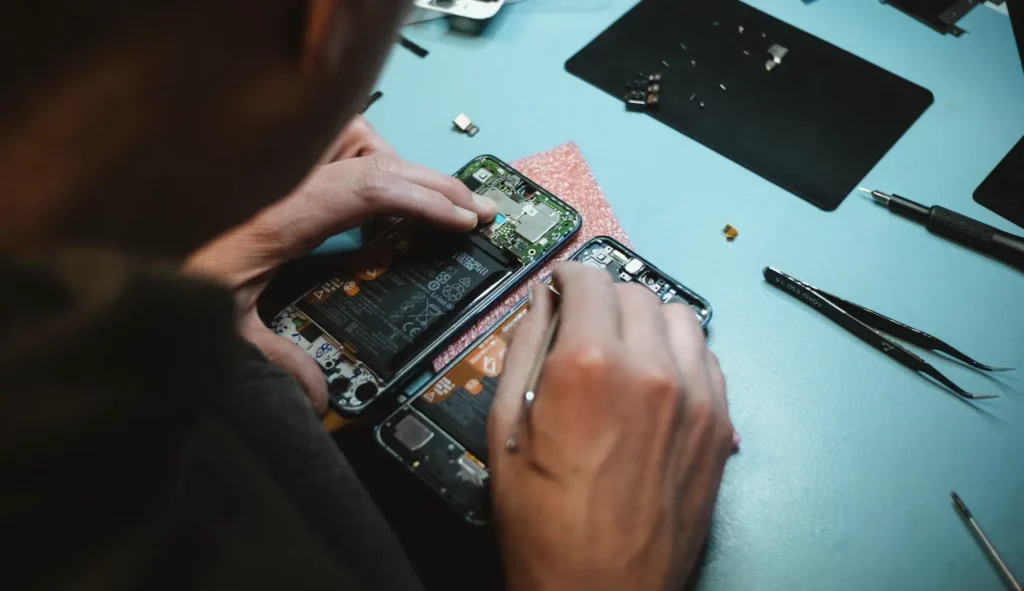

If a single chip on a logic board fails, the repair shop can’t simply buy that chip. They must harvest it from another ‘donor’ laptop.

From both environmental and business perspectives, this isn’t sustainable. Donor laptops are not always available.

It takes time to harvest working components from a broken machine. Repair shops cannot buy in bulk, making it hard to operate at scale.

Consumers are thereby forced to pay more for simple repairs. The cost of replacing a single defective board-level chip is always lower than replacing the entire logic board.

But if a repair shop must first harvest a working chip from a donor machine, the price a consumer will pay must reflect that.

In some cases, where a repair shop cannot source a working component, the consumer is forced to use a vendor-sanctioned repair shop (in this case, the Apple Store or an Apple-approved provider).

The Cost to the Consumer

These certified vendors rarely — if ever — perform board-level repairs. They just yank the defective component and install a new one.

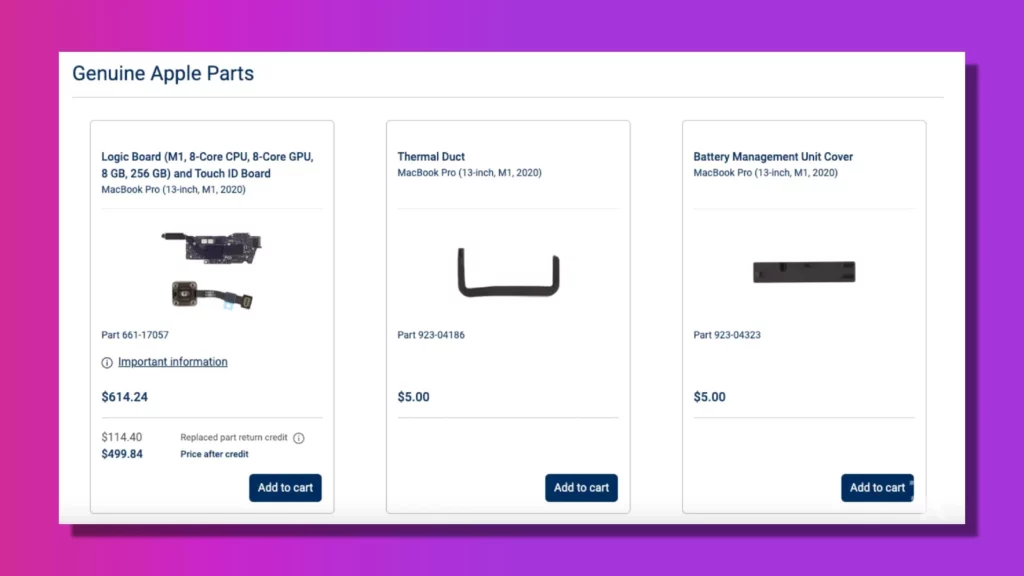

This presents two problems. First: the cost. A replacement M1 MacBook Pro logic board costs $614.24. Consumers must pay that, even if the issue only lies with a single $1 chip.

In fairness to Apple, it refunds $114.40 if the consumer repairs the defective logic board, bringing the price down to under $500. But that’s still a lot of money.

The second problem is also the biggest. With most modern Macs, Apple solders the flash storage chips directly onto the logic board. It’s not a user-replaceable component.

Or, put another way: if a $1 chip fails on your Mac and it can’t power on, you’ll lose all your data.

Apple isn’t the only company selling non-upgradable devices. And its approach has some technical advantages.

The Unified Memory design used in the latest M1 and M2 Macs has serious performance advantages over conventional approaches.

But it also makes disaster recovery incredibly hard. Apple could address this by opening its supply chain to third parties. But it doesn’t.

The Problem of Serialization

Independent repair shops routinely harvest working components from dead machines. It’s normal practice, albeit one made necessary by Apple’s unwillingness to share components with third parties.

In recent years, Apple has sought to stop this practice using serialization.

Serialization is, in short, using software to link individual components to a device. It’s a way of saying “this camera module belongs to this logic board.”

In some cases, there are legitimate reasons for this. I can understand why Apple serializes the iPhone’s Touch ID module. It’s used to conduct financial transactions, authenticate online services, and so on.

But Apple also serializes other components, too. With the iPhone 12, Apple linked the display and camera module to the connected logic board.

If a repair shop transplants a camera module from one phone to another, it’ll malfunction. The camera app will freeze during use. Users are unable to switch to the ultra-wide camera. The entire photography experience becomes degraded.

Additionally, Donor displays cannot use FaceID or Truetone. While the first example is (vaguely) reasonable, the latter is not.

The only way around this is with Apple’s proprietary repair software, which it restricts to internal and authorized repair providers.

In most cases, serialization doesn’t protect consumers. It is merely an artificial limitation on what independent repair shops can do.

It’s a naked attempt to limit consumer choice and shrink a (vocal) sector of the repair economy.

The Tip of the Iceberg

I’ve only really scratched the service here. Apple’s right-to-repair sins are numerous. This article lists just a few.

I could have, for example, discussed how Apple stops third-party manufacturers from selling compatible replacement components without their consent.

In 2020, Apple successfully sued Henrik Huseby, an independent repair provider, over allegations he imported “counterfeit” iPhone screens. Huseby never claimed to use genuine components.

The displays in question were actually refurbished components acquired from a Chinese manufacturer. The supplier acquired original (albeit smashed) iPhone screens, removed and replaced the broken glass, and resold them.

Norway’s Supreme Court ruled against Huseby and ordered him to pay $23,000 to Apple. This punishment was wildly disproportionate to the alleged ‘offense.’ Huseby imported just 63 displays.

As such, I can’t bring myself to be excited about Apple’s Mac self-repair program. It’s a step in the right direction. But it doesn’t overshadow Apple’s appalling behavior, both in the past and now.

Have any thoughts on this? Carry the discussion over to our Twitter or Facebook.

Editors’ Recommendations:

- What does the “i” in iPhone (or iPad) mean?

- eBay’s rules for refurbished tech terrify right-to-repair activists

- Samsung will finally let you repair your own Galaxy smartphone

- Apple says it will no longer repair stolen iPhones at Apple Stores